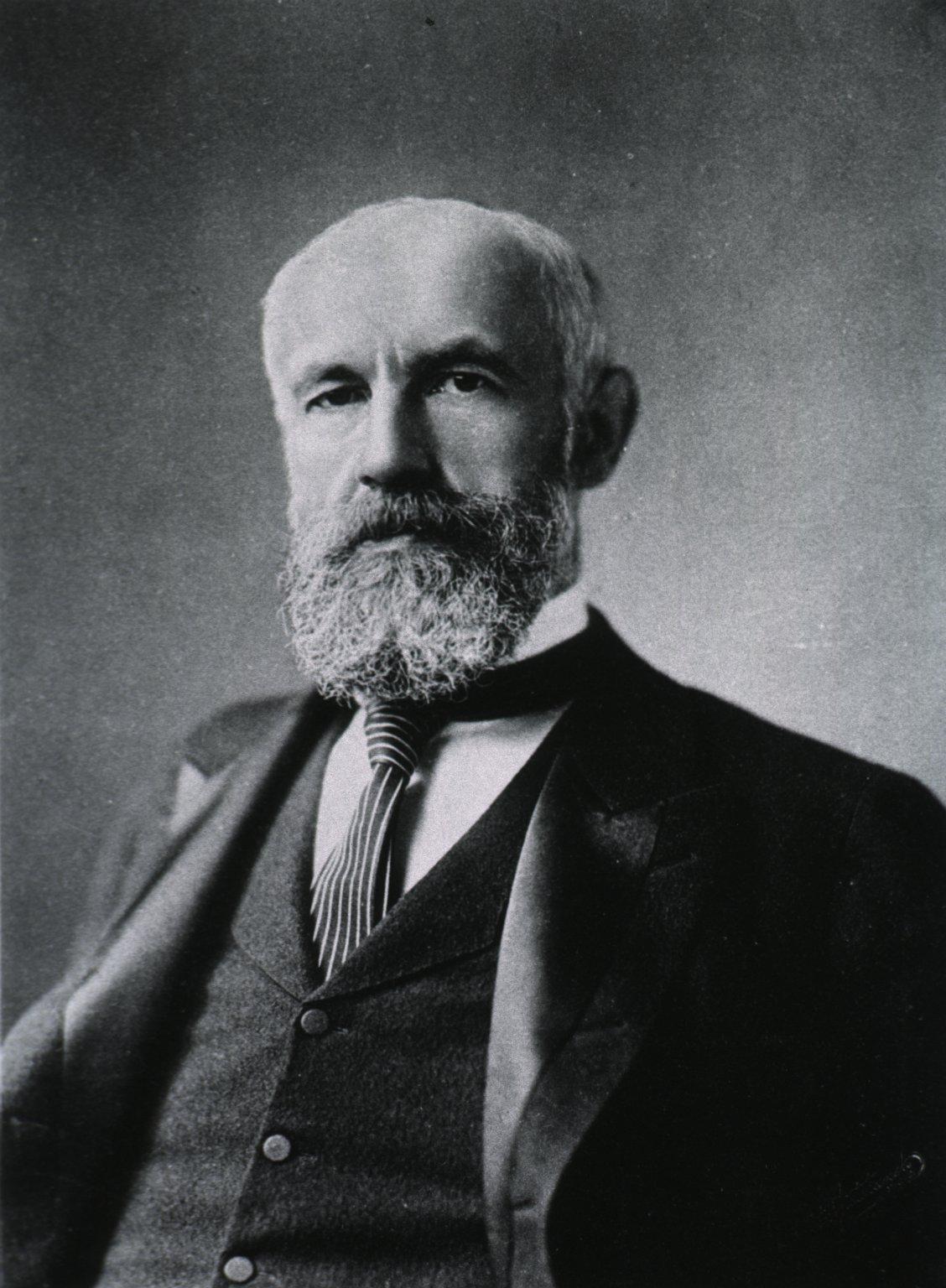

G. Stanley Hall

A Founding Father of Developmental Psychology and the “Father of Adolescence”

Granville Stanley Hall (1844-1924) was a monumental figure in American psychology and education, widely recognized as a founding father of developmental psychology and, most famously, the “father of adolescence.” He was a driving force behind establishing psychology as a scientific discipline in the United States, founding the first American psychology laboratory at Johns Hopkins University in 1883 and serving as the first president of the American Psychological Association (APA) in 1892.

Hall’s early and most prominent work was heavily influenced by evolutionary theory, specifically the (now largely discredited) concept of recapitulation theory, adapted from biologist Ernst Haeckel.

Recapitulation Theory in Development

Hall applied Haeckel’s “biogenetic law” (“ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny”—that is, individual development repeats the evolutionary history of the species) to psychological development. He posited that children’s psychological growth mirrored the evolutionary stages of the human race. For example:

-

Infancy was likened to the primitive, animalistic stage of humanity.

-

Childhood was seen as a re-enactment of the savage, nomadic hunter-gatherer existence.

-

Adolescence represented the transition from barbarism to civilization, a period of significant upheaval and potential.

While this theory is no longer accepted, it provided the framework for his extensive investigations into development.

The Concept of Adolescence as “Storm and Stress”

Hall’s most significant and enduring contribution to developmental psychology was his comprehensive focus on adolescence as a distinct and crucial stage of human life. His groundbreaking two-volume work, Adolescence: Its Psychology and Its Relations to Physiology, Anthropology, Sociology, Sex, Crime, Religion, and Education (1904), was pivotal in establishing this period as a legitimate field of study.

In this seminal work, Hall famously introduced the concept of “storm and stress” (Sturm und Drang) to characterize adolescence. He proposed that this stage is naturally and universally marked by three key characteristics:

-

Conflict with parents: Driven by a burgeoning desire for independence and autonomy.

-

Mood disruptions: Experiencing heightened emotional intensity and rapid shifts between extreme states of happiness, sadness, and anger.

-

Risky behavior: Engaging in impulsive actions, sensation-seeking, and a willingness to challenge norms.

Hall believed these elements were biologically determined and a necessary part of the developmental process. While contemporary research has refined this view, demonstrating that “storm and stress” is not universal and varies greatly among individuals and cultures, Hall’s articulation of it profoundly influenced how society and science perceive and study adolescence.

Pioneering the Lifespan Perspective, Especially on Aging

Beyond his focus on childhood and adolescence, Hall was also a remarkably forward-thinking pioneer in advocating for a lifespan developmental perspective, even though the term itself wasn’t fully coined until much later. His interest extended to the latter stages of life, a topic largely neglected by psychologists of his era.

In his final major work, Senescence: The Last Half of Life (1922), published just two years before his death, Hall embarked on one of the first systematic psychological studies of aging in the United States. In this book, he explored a wide range of topics related to old age, including:

-

Physiological changes: Discussing the physical decline associated with aging.

-

Cognitive changes: Examining alterations in memory, learning, and intellectual functioning.

-

Emotional and social adjustments: Exploring the psychological challenges and adaptations associated with retirement, loss of loved ones, changing social roles, and confronting mortality.

-

The potential for continued growth and wisdom: Despite acknowledging the declines, Hall also highlighted the potential for wisdom, introspection, and new forms of engagement in later life, a perspective that prefigured much later positive psychology on aging.

Through Senescence, Hall laid foundational groundwork for what would become the field of gerontology and developmental psychology of aging. By turning his scientific lens to both the beginning and the end of life, he implicitly argued for the importance of studying the entire human lifespan. While his methods and some conclusions in Senescence reflect the limitations of early 20th-century psychology, his foresight in recognizing aging as a legitimate and important domain for psychological inquiry was truly groundbreaking, underscoring his comprehensive vision for the field of human development.

Other Notable Contributions

-

Child Study Movement: Hall was a central figure in this movement, advocating for empirical observation and systematic data collection on children to inform educational practices.

-

Educational Reform: He championed child-centered education, believing that schooling should be tailored to the natural developmental stages and needs of the child.

-

Establishment of Psychology: His founding of the first American psychology laboratory and his leadership in the APA were crucial for the professionalization of psychology in the U.S.

In summary, G. Stanley Hall was a monumental figure whose work defined adolescence as a distinct stage and significantly contributed to the empirical study of development. Critically, his later work on aging showcased his forward-thinking vision for a psychology that encompassed the entire human lifespan, laying important groundwork for future generations of developmental psychologists.