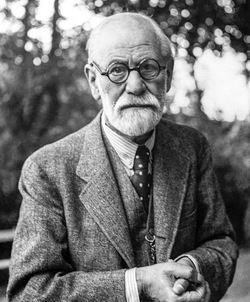

Sigmund Freud

The Father of Psychoanalysis

Sigmund Freud was an Austrian neurologist who founded psychoanalysis, a clinical method for treating psychopathology through dialogue between a patient and a psychoanalyst. His theories, while highly controversial and heavily debated, fundamentally transformed Western thought regarding the human mind, personality, and psychological development. While he did not focus explicitly on “adult development” as a continuous process in the same way later lifespan theorists did, his theories of early childhood development lay the crucial groundwork for adult personality and psychopathology. He believed that the foundations of adult personality are largely established in early childhood.

Key Concepts and Contributions:

-

Levels of Consciousness: Freud proposed that the mind operates on three levels:

-

Conscious: What we are currently aware of.

-

Preconscious: Information that is not currently in awareness but can be easily retrieved (e.g., a memory).

-

Unconscious: The vast reservoir of thoughts, feelings, memories, and desires that are hidden from conscious awareness but profoundly influence our behavior. Freud believed the unconscious was the primary determinant of personality and behavior.

-

Structure of Personality (The Id, Ego, and Superego): Freud posited a tripartite model of personality:

-

Id: The primitive, instinctual part of the personality. It operates on the pleasure principle, seeking immediate gratification of urges and desires (e.g., hunger, thirst, sex, aggression). It is entirely unconscious.

-

Ego: The rational, reality-oriented part of the personality. It operates on the reality principle, mediating between the demands of the id, the constraints of reality, and the moral demands of the superego. It is partly conscious, preconscious, and unconscious.

-

Superego: The internalized moral component of personality, representing societal and parental standards of right and wrong. It strives for perfection, judging our actions and producing feelings of pride or guilt. It develops through identification with parents and is partly conscious, preconscious, and unconscious.

-

Dynamic Interaction: Freud believed that psychological health depends on a dynamic balance among these three structures. Conflicts between the id, ego, and superego can lead to anxiety and psychological distress.

-

Psychosexual Stages of Development: Freud argued that personality development occurs through a series of psychosexual stages, each characterized by a particular erogenous zone (a part of the body that serves as the focus of pleasure and gratification). Conflicts or unmet needs at any stage can lead to fixation, where an individual remains “stuck” in certain behaviors or personality traits associated with that stage in adulthood.

-

Oral Stage (Birth to 1 year): Focus on the mouth (sucking, biting, feeding). Fixation can lead to oral-dependent (overly trusting, passive) or oral-aggressive (sarcastic, argumentative) adult personalities.

-

Anal Stage (1 to 3 years): Focus on bowel and bladder control. Fixation can lead to anal-retentive (orderly, stingy, obstinate) or anal-expulsive (messy, rebellious) adult personalities.

-

Phallic Stage (3 to 6 years): Focus on the genitals; emergence of sexual curiosity and awareness of gender differences. This stage involves the Oedipus complex (boys’ sexual desire for their mother and rivalry with their father) and the Electra complex (girls’ desire for their father and penis envy). Resolution involves identification with the same-sex parent.

-

Latency Stage (6 to puberty): A period of dormant sexual feelings; focus on social and intellectual development, forming same-sex friendships.

-

Genital Stage (Puberty onward): Maturation of sexual interests, seeking mature, reciprocal intimate relationships. This is the goal of healthy adult development for Freud, where previously fixated energy is redirected towards productive and loving ends.

-

Defense Mechanisms: To cope with anxiety arising from conflicts between the id, ego, and superego, the ego employs defense mechanisms (unconscious strategies that distort reality). Examples include:

-

Repression: Pushing threatening thoughts into the unconscious.

-

Denial: Refusing to acknowledge an anxiety-provoking reality.

-

Projection: Attributing one’s own unacceptable impulses to others.

-

Displacement: Redirecting impulses from a threatening target to a less threatening one.

-

Sublimation: Channeling unacceptable impulses into socially acceptable behaviors (considered a mature defense).

Freud’s Impact on Understanding Adult Development:

While he didn’t outline a lifespan model, Freud’s central premise was that adult personality and psychological well-being are largely determined by early childhood experiences and the successful (or unsuccessful) resolution of conflicts in the psychosexual stages. Adult neuroses, personality traits, and patterns of relating are seen as echoes or manifestations of unresolved childhood conflicts or fixations. Psychoanalysis, as a therapeutic method, aims to bring unconscious conflicts into conscious awareness to resolve them and alleviate adult suffering.

Legacy and Critique:

Freud’s theories were revolutionary and laid the groundwork for much of modern psychology. He brought attention to the power of the unconscious, the importance of early childhood, and the dynamic nature of personality. However, his work has also faced significant criticism for:

-

Lack of empirical testability: Many of his concepts are difficult to prove or disprove scientifically.

-

Overemphasis on sexuality: Critics argue he placed too much importance on sexual drives as the primary motivator.

-

Limited generalizability: His theories were largely based on observations of a small number of emotionally disturbed, upper-class Viennese patients.

-

Sexism: Accused of being male-centric and devaluing female experience (e.g., penis envy).

Despite these critiques, Freud’s influence on psychology, psychiatry, literature, and popular culture is undeniable. His concepts of the unconscious, defense mechanisms, and the enduring impact of childhood experiences remain foundational, even if his specific stage theory has been significantly revised or superseded by later developmental models.