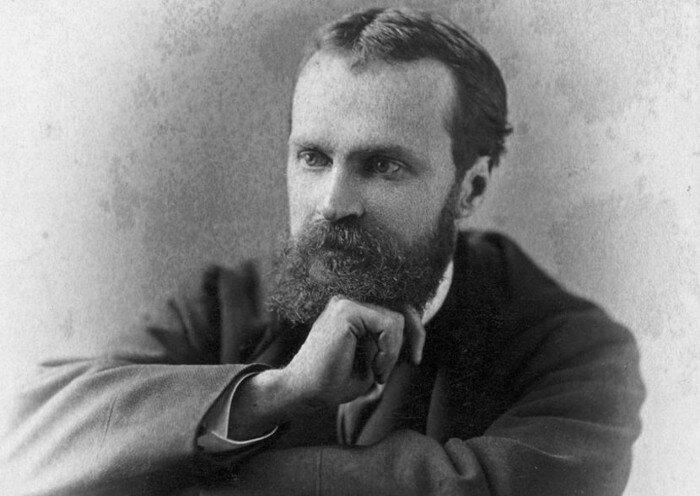

William James

The Father of American Psychology and Functionalism

William James (1842-1910) was a towering figure in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, widely regarded as the “Father of American Psychology” and a foundational figure in the philosophical school of Pragmatism. His monumental 1890 work, The Principles of Psychology, laid much of the groundwork for modern psychological thought. While not a “developmental psychologist” in the sense of proposing explicit stage theories for the entire lifespan, his profound insights into consciousness, the self, and habit formation have strong, often indirect, implications for understanding development across all ages, including adulthood.

Key Contributions Relevant to Development:

-

Functionalism: James’s approach to psychology, known as Functionalism, emphasized the purpose and function of mental processes, rather than just their structure (in contrast to Structuralism). He was deeply influenced by Darwin’s theory of evolution, believing that mental processes and behaviors that enhance survival and adaptation are more likely to be passed on. This focus on how mental activities help individuals adapt to their environment inherently has developmental implications, as adaptation is a continuous process throughout life.

-

The Stream of Consciousness: James famously described consciousness not as a series of discrete thoughts but as a continuous, ever-flowing, personal, changing, selective, and active “stream of consciousness.”

-

Relevance to Development: This concept highlights the dynamic and fluid nature of mental life, which is constantly evolving and adapting. For adult development, it suggests that our understanding of ourselves and the world is not static but a continuous, subjective construction that changes with experience and reflection. The “stream” perspective implies ongoing processing and integration of new experiences, rather than fixed stages.

-

The Concept of the Self: James offered a complex and influential theory of the self, distinguishing between the “I” and the “Me”:

-

The “I” (The Pure Ego/Self as Knower): This is the subjective self, the awareness of one’s own existence, the “thinker” or the “doer.” It provides the sense of personal identity and continuity across time.

-

The “Me” (The Empirical Self/Self as Known): This is the objective self, what one knows about oneself. James further divided the “Me” into three hierarchical components:

-

Material Self: Comprises one’s body, possessions, family, and tangible things one calls “mine” (e.g., clothes, home, money).

-

Social Self: Refers to how we are recognized and perceived by others. James argued we have as many social selves as there are distinct groups of people who recognize us. Our behavior often changes depending on the social context.

-

Spiritual Self: The innermost core of the self, encompassing one’s personality, core values, moral conscience, and inner thoughts and feelings. This is considered the most enduring and permanent aspect.

-

Relevance to Development: James’s theory of the self is profoundly developmental. It suggests that the self is multifaceted and dynamic, constantly developing through interactions with the environment and reflections on one’s experiences. The material, social, and spiritual selves continue to evolve and seek affirmation throughout adulthood. The constant negotiation between these different “selves” is a lifelong psychological process.

-

Habit Formation: James placed immense importance on the formation of habits. He viewed habits as ingrained patterns of behavior that become automatic through repetition, leading to greater efficiency and freeing up conscious attention for more complex tasks.

-

Relevance to Development: For James, character is largely a “bundle of habits.” He argued for the conscious cultivation of good habits and the systematic breaking of bad ones, particularly in early life, as this foundation shapes one’s adult life. However, he also recognized that adults could deliberately form new habits or modify old ones, emphasizing the power of conscious effort and self-discipline to shape one’s adult trajectory. His insights into habit formation are still highly relevant to understanding adult learning, behavior change, and the development of expertise.

William James’s Place in Developmental Psychology:

While James did not present a formal, sequential stage model of development spanning the lifespan like some later theorists, his ideas were foundational to the very spirit of developmental inquiry. He championed the study of mental processes in their natural context and how they serve adaptive functions, which are central tenets of developmental psychology. His concepts of the evolving self, the dynamic nature of consciousness, and the power of habit formation provided crucial building blocks for subsequent theories of personality, social development, and adult learning. He viewed the human being as an active, adaptive agent constantly interacting with and being shaped by their environment, a perspective that underpins much of contemporary developmental thought.