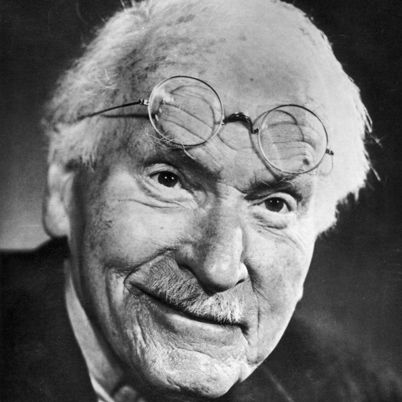

Carl Jung

The Founder of Analytical Psychology

Carl Jung (1875-1961) was a Swiss psychiatrist and the founder of Analytical Psychology. While initially a close associate of Sigmund Freud, Jung eventually diverged sharply, particularly in his understanding of the unconscious and the trajectory of human development. A central tenet of his work, and arguably his most significant contribution to adult development, is his emphasis on the second half of life as a period of profound and necessary psychological transformation.

The Stages of Life (with emphasis on Adulthood)

Jung often spoke of life using the metaphor of the sun’s trajectory across the sky, with different phases having distinct psychological aims:

-

Childhood to Early Adulthood (The Morning of Life): This period, roughly from birth to around age 35-40, is characterized by ego development and adaptation to the outer world. The individual is primarily focused on establishing their place in society, building a career, forming a family, and developing a persona (the social mask we present to the world). Psychic energy (libido) is largely directed externally, striving for concrete achievements and fitting into societal norms. Jung believed this was a necessary phase for establishing a strong ego and a stable foundation.

-

Midlife (The Midday Point): Around ages 35-40, Jung observed a significant shift. This period often presents as a crisis – not necessarily a breakdown, but a profound turning point where the values and goals that motivated the first half of life begin to lose their meaning or seem insufficient. Individuals may feel a sense of disillusionment, a questioning of purpose, or an emergence of previously neglected aspects of their personality. Jung saw this as a natural and essential transition, not a pathology, which signals a necessary redirection of psychic energy.

-

Midlife to Old Age (The Afternoon and Evening of Life): This is the period of intense focus on inner growth and self-realization, a process Jung called individuation. Psychic energy shifts from an outward to an inward direction. The individual begins to reconcile and integrate previously disparate or unconscious parts of the psyche.

Individuation: The Lifelong Journey to Wholeness

Individuation is the cornerstone of Jung’s theory of adult development, particularly in the second half of life. It is defined as the process by which an individual becomes a unified, unique, and whole person. It involves:

-

Integration of Opposites: Life, for Jung, is characterized by inherent polarities (conscious/unconscious, masculine/feminine, good/evil, light/shadow). Individuation is the process of acknowledging, confronting, and integrating these opposing forces within the psyche, rather than repressing or disowning them.

-

Confrontation with the Unconscious: This process necessitates turning inward and engaging with the contents of both the personal unconscious (repressed memories, forgotten experiences, subliminal perceptions) and the collective unconscious (a deeper, inherited layer of the psyche containing universal archetypes).

-

The Shadow: Confronting the “shadow” (the unconscious, disowned aspects of the personality, both negative and sometimes positive potentials) is a crucial step. Integrating the shadow means acknowledging these parts of oneself rather than projecting them onto others.

-

Anima/Animus: Integrating the “anima” (the unconscious feminine aspect in men) and the “animus” (the unconscious masculine aspect in women) leads to greater psychological completeness and a richer capacity for relationships.

-

Decentering the Ego and Connecting with the Self: While a strong ego is vital for navigating the first half of life, individuation requires the ego to loosen its dominant grip and become subservient to the Self. The Self is Jung’s most inclusive archetype, representing the totality of the psyche, the organizing center of personality, and the blueprint for wholeness. It is not the ego but a transcendent reality that encompasses both conscious and unconscious. Through individuation, the ego aligns with the Self, leading to a deeper sense of meaning and purpose.

-

Meaning-Making and Spirituality: Jung believed that the search for meaning, often taking on a spiritual or philosophical dimension, becomes paramount in the second half of life. He observed that many older patients who found psychological healing did so by developing a “spiritual outlook.” This inner quest allows individuals to transcend purely material goals and find connection to something larger than themselves.

Significance for Adult Development:

Jung’s work was revolutionary in several ways:

-

Affirmed the Value of Later Life: He was one of the first to articulate that the second half of life is not merely a period of decline but a vital stage with its own unique developmental tasks and immense potential for psychological and spiritual growth.

-

Normalized Midlife Transitions: By describing midlife as a necessary turning point for self-reorientation, he offered a psychological framework for understanding experiences that might otherwise be dismissed as mere “crisis.”

-

Introduced Depth and Archetypal Dimensions: His theories provided a richer, more symbolic, and transpersonal understanding of human experience, emphasizing the interplay of archetypes and the collective unconscious in shaping our journey towards wholeness.

-

Emphasized Interiority: He stressed the critical importance of introspection, self-reflection, and inner work as pathways to psychological maturity in adulthood.

In essence, Carl Jung provided a compelling vision of adult development as a continuous, often challenging, but ultimately purposeful journey towards becoming the most authentic and integrated version of oneself – a journey that reaches its peak in the profound psychological transformations of the second half of life.