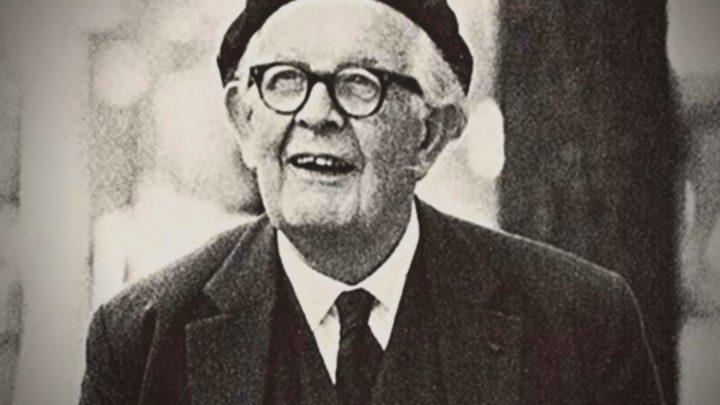

Jean Piaget

Genetic Epistemology: The Study of Knowledge Development

Jean Piaget (1896-1980) was a Swiss developmental psychologist and philosopher who is arguably the most influential figure in the field of cognitive development. His groundbreaking work fundamentally changed how we understand children’s thinking, shifting from the view of children as miniature adults to recognizing them as active, constructive learners with qualitatively different thought processes at different ages.

Genetic Epistemology: The Study of Knowledge Development

Piaget referred to his broad theory as genetic epistemology, which is the study of the origins of knowledge. He was interested not just in what children know, but how they come to know it, tracing the development of thought processes from infancy to adulthood. He believed that intelligence is a form of adaptation to the environment, much like biological adaptation.

Core Concepts of Piaget’s Theory

Piaget proposed that children build their understanding of the world through an active process of constructing knowledge. This construction involves key concepts:

-

Schemas (or Schemata): These are the basic building blocks of intelligent behavior—mental structures or organized patterns of thought and action that individuals use to make sense of and interact with the world. A schema can be a simple reflex (like sucking) or a complex concept (like justice). As children develop, their schemas become more numerous, complex, and integrated.

-

Adaptation Processes: Piaget believed cognitive development is driven by a continuous process of adaptation to the environment, which involves two complementary mechanisms:

-

Assimilation: The process of incorporating new information or experiences into existing schemas. For example, a baby who has a “grasping” schema might try to grasp a new toy, fitting it into their existing understanding.

-

Accommodation: The process of modifying or creating new schemas to fit new information that doesn’t neatly fit into existing ones. If the toy is too large to grasp with the existing schema, the baby might accommodate by developing a new way to interact with it (e.g., using two hands).

-

Equilibration: This is the driving force behind cognitive development. It’s the process of seeking cognitive balance between assimilation and accommodation. When a child encounters new information that creates a “disequilibrium” (a mismatch between what they know and what they are experiencing), they are motivated to restore balance by either assimilating the new information or accommodating their schemas. This dynamic interplay leads to cognitive growth.

Four Stages of Cognitive Development

Piaget proposed that children universally progress through four distinct, sequential stages of cognitive development. Each stage represents a qualitatively different way of thinking and is characterized by specific cognitive abilities and limitations:

-

Sensorimotor Stage (Birth to approximately 2 years):

-

Infants understand the world primarily through their senses and motor actions (e.g., looking, touching, grasping, sucking).

-

Key achievement: Object Permanence—the understanding that objects continue to exist even when they are out of sight. Before this, “out of sight, out of mind” truly applies.

-

Development of goal-directed behavior and basic imitation.

-

Preoperational Stage (Approximately 2 to 7 years):

-

Children begin to use symbols (language, mental images, pretend play) to represent objects and ideas.

-

Thinking is characterized by:

-

Egocentrism: Difficulty seeing the world from another person’s perspective.

-

Centration: Tendency to focus on only one salient aspect of a situation, neglecting others.

-

Lack of Conservation: Inability to understand that the quantity of a substance remains the same despite changes in its appearance (e.g., the classic liquid conservation task).

-

Animism: Attributing human qualities to inanimate objects.

-

Concrete Operational Stage (Approximately 7 to 11 years):

-

Children develop logical thinking about concrete events and objects.

-

They master conservation (number, mass, volume), demonstrating an understanding of reversibility and decentration.

-

Can perform mental operations if they involve concrete objects or situations (e.g., sorting, classifying, seriation).

-

Thinking is still limited; they struggle with abstract or hypothetical reasoning.

-

Formal Operational Stage (Approximately 11-12 years and into adulthood):

-

Adolescents and adults gain the ability to think abstractly, hypothetically, and systematically.

-

They can engage in hypothetico-deductive reasoning (formulating hypotheses and systematically testing them).

-

Can consider multiple perspectives and engage in complex problem-solving.

-

Piaget believed not all individuals fully achieve this stage or apply it consistently in all areas of their lives.

Impact and Legacy

Piaget’s influence on developmental psychology and education is immense:

-

Pioneered the Scientific Study of Children’s Thinking: He was among the first to systematically observe and interview children to understand their reasoning.

-

Child as Active Learner (Constructivism): His theory championed the view that children are not passive recipients of information but actively construct their own knowledge through interaction with their environment. This underpins modern constructivist approaches to education.

-

Influenced Education: His work led to significant changes in educational practices, emphasizing child-centered learning, discovery learning, and tailoring instruction to a child’s developmental readiness.

-

Inspired Further Research: While his theory has faced critiques (e.g., underestimating children’s abilities, overemphasis on stages, neglecting social/cultural factors), it has served as a foundational framework for countless subsequent research studies and alternative theories (like the neo-Piagetians, sociocultural theorists like Vygotsky).

Jean Piaget revolutionized our understanding of how children think and learn, leaving an indelible mark on psychology, education, and our broader understanding of human development.