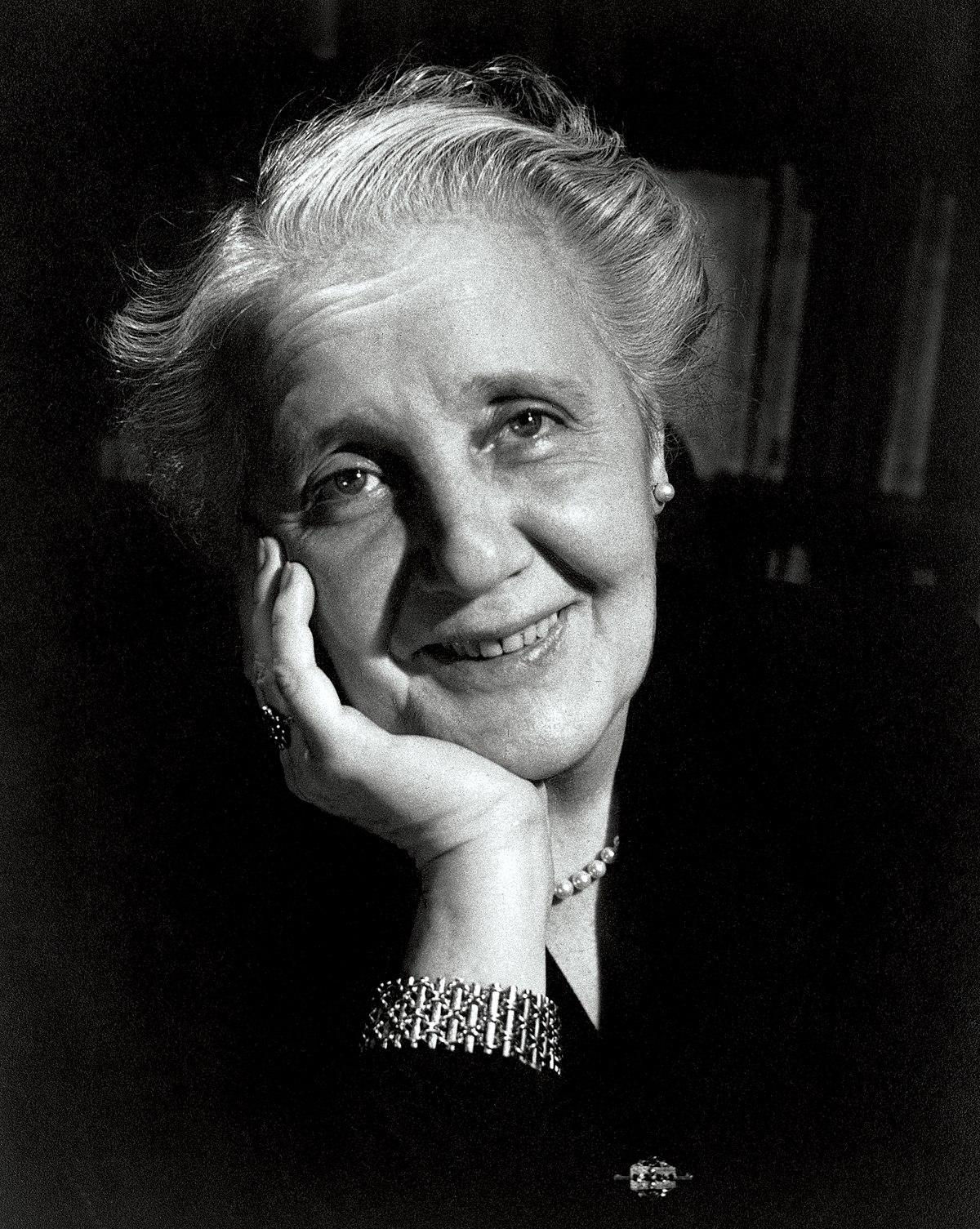

Melanie Klein

The Architect of Object Relations Theory and Early Psychic Life

Melanie Klein (1882-1960) was an Austrian-born British psychoanalyst whose radical theoretical contributions profoundly reshaped psychoanalysis, particularly by focusing on the earliest stages of infant development and the crucial role of internalized relationships (“objects”). While her primary clinical work and theoretical elaborations centered on infants and young children (often through her pioneering “play technique”), her concepts provide a deep and enduring framework for understanding the foundations of adult personality, psychopathology, and relationship patterns.

Klein’s major departure from classical Freudian theory was her emphasis on innate aggressive drives (derived from the death instinct) from birth, and how the infant’s ego, though rudimentary, actively attempts to manage intense anxieties arising from these aggressive impulses and the frustrations of early life.

Key Contributions Relevant to Adult Development:

-

Object Relations Theory: Klein is considered the primary figure in Object Relations Theory. Unlike Freud, who emphasized the gratification of drives, Klein argued that humans are primarily motivated by a fundamental need to form relationships with others (“objects”). These “objects” are not just external people but also their internalized mental representations, which are often experienced as “part-objects” (e.g., the “good breast” that feeds, the “bad breast” that frustrates) before the infant can perceive a whole person.

-

Relevance to Adults: The way infants relate to and internalize these early “objects” (primarily the mother or primary caregiver) creates internal blueprints for all future relationships and deeply shapes adult personality. Maladaptive patterns in adult relationships, difficulties with intimacy, attachment issues, or even personality disorders are often understood in Kleinian thought as manifestations of unresolved or pathological early object relations. Adults unconsciously project these internalized “objects” onto current relationships, leading to repetitive interpersonal dynamics.

-

The Paranoid-Schizoid Position: This is Klein’s earliest developmental “position” (a way of experiencing the self and others, which can be returned to throughout life), typically characterizing the first 3-4 months of life. It is driven by intense persecutory anxiety (fear of annihilation or attack, largely from internalized aggressive impulses projected outward).

-

Key Defenses: The ego copes with this overwhelming anxiety through splitting (mentally separating objects and feelings into “all good” and “all bad” to protect the “good” parts from the “bad” ones) and projective identification (projecting unwanted parts of the self or feelings into another person, unconsciously inducing those feelings in them).

-

Relevance to Adults: While most individuals move beyond the dominance of this position, its mechanisms can be reactivated in adulthood, especially under stress, trauma, or in specific psychopathologies (e.g., borderline personality disorder, paranoid states). An adult who consistently splits others into “all good” or “all bad,” or who frequently projects their own unwanted feelings onto others, might be understood as predominantly operating from a paranoid-schizoid mode of relating.

-

The Depressive Position: Normally emerging around 4-6 months and continuing to be worked through throughout life, this position marks a crucial developmental leap. The infant begins to integrate the “good” and “bad” aspects of the object (e.g., recognizing that the gratifying mother is also the frustrating mother, and that they are one and the same person). This leads to the capacity for whole object relations.

-

Key Anxieties and Defenses: The primary anxiety shifts from fear of persecution to depressive anxiety—a fear of having harmed or destroyed the loved whole object through one’s own aggressive impulses. This brings about guilt, sorrow, and the urge for reparation (making amends or restoring good relations).

-

Relevance to Adults: The ability to achieve and maintain the depressive position in adulthood is central to psychological maturity. It allows for:

-

Genuine empathy and concern for others: Recognizing others as complex individuals with both good and bad qualities.

-

Capacity for guilt and remorse: Taking responsibility for one’s own destructive impulses or actions.

-

Motivation for reparation: The desire to repair relationships, contribute constructively, and make amends.

-

Resilience in the face of loss: The ability to mourn losses without being overwhelmed by despair.

-

Klein believed that individuals who struggle to fully integrate the depressive position in childhood might experience chronic guilt, difficulties with mourning, or an inability to form deep, stable, and reciprocal adult relationships.

-

Envy and Gratitude: Klein emphasized the innate nature of envy (the feeling of wanting to spoil or destroy another’s goodness, especially when that goodness is perceived as superior) and gratitude (the appreciation for good experiences and objects, which helps in integrating “good” internal objects).

-

Relevance to Adults: These primal emotions continue to play a role in adult relationships and personal well-being. Excessive envy can undermine satisfaction, foster resentment, and impede the ability to receive help or appreciate others’ successes. The capacity for gratitude, conversely, supports healthy self-esteem, robust relationships, and resilience.

In essence, Melanie Klein’s profound contribution to adult development lies in her radical assertion that the most complex and fundamental patterns of adult personality, relationship dynamics, and psychopathology are established in the earliest months of infancy. Her Object Relations Theory and concepts of the paranoid-schizoid and depressive positions offer a powerful lens through which to understand the enduring impact of primal anxieties, defenses, and internalized relationship blueprints on the entirety of the human psychological journey.